Curation in the arts has been written about from so many academic view points, it’s common for artists to feel a little daunted by the task. However, if you look at curating your artwork from a pragmatic view point, it’s something all of us are able to do and can be a really fun part of the job.

Let’s start by simplifying what curation is. In her book, ‘How to tell your story so the world listens’, Hollywood story consultant Bobette Buster uses the term ‘the story behind the story’ which refers to the hidden, deeper narrative that’s holding everything together. This is a great metaphor for how to approach curation.

Good curation, like good storytelling, gives your work a coherent vision or narrative that can entertain, inspire, educate, etc. This doesn’t mean that curation has to be centered around an explicit theme. Ideas can be loose, abstract or loaded with multiple meanings, and the benefit of visual art is it allows us to communicate these themes on an instinctive level.

The many different ways of showing work means there is no single approach to curation, but there are some universal considerations that will help to guide you. Here are four things you should think about:

Themes

Defining a theme, loose or explicit, can help shape the rest of the curatorial process and can help with the promotional side of the exhibition as it helps potential visitors and the media to contextualise it.

Take David Hockney’s 2009-2012 iPhone & iPad drawings. He tackles some similar subject matter to his previous works. However they are grouped by the medium he has used to create them, so the medium and his artistic technique in this case is the main curatorial theme. There is a topical aspect to the theme also given that he is exploring the possibilities of this new technological medium at a time of unprecedented technological development.

Another example is Martin Parr’s recent exhibition, Only Human, which showed at the National Portrait Gallery. This exhibition brought together images that spanned decades of Parr’s career. It mixed portraits, landscapes and street scenes, yet it was tied together with the themes of people and cultural and national identity. These themes were very topical as the exhibition took place against the backdrop of the Brexit debate, which was raging in nearby parliament and across the country. Any theme that hits topical notes is primed to gain more attention in the media.

With themes, the possibilities are endless. For example, they can

be social, political, philosophical, aesthetic by nature, or based around an art movement or medium. They could be more linear, such as the chronology or progression of the artist or artists, subject matter or body of work being shown. And narratives embedded in the curation can, for example, be linear, explicit, abstract, subliminal or non-existent.

Space

The space you have to work with can shape your curation, and can be used to guide the viewer through it. Take two exhibitions held at the Hayward Gallery; Carsten Höller: Decision (2015/16), and Diane Arbus: In the beginning (2019). Carsten’s show was about perception and decision making which he incorporated into the space. At the start of the exhibition visitors were given a choice of two different entrances, which lead to separate routes through the gallery each with different choices and interactions along the way. Diane Arbus’ show was a collection of her early rare works presented in a more traditional layout. Each photograph was framed and hung on the wall with equal space and severity and there was one entrance and exit to the show.

On both these occasions, the space was manipulated to guide the visitor through the exhibition in a way which mirrored the artist and their work. Had Carsten’s show been displayed in a ‘white cube’ setting the impact of the show would have been different. In contrast, the curation of Arbus’ exhibition was designed to put the focus purely on the content of the images.

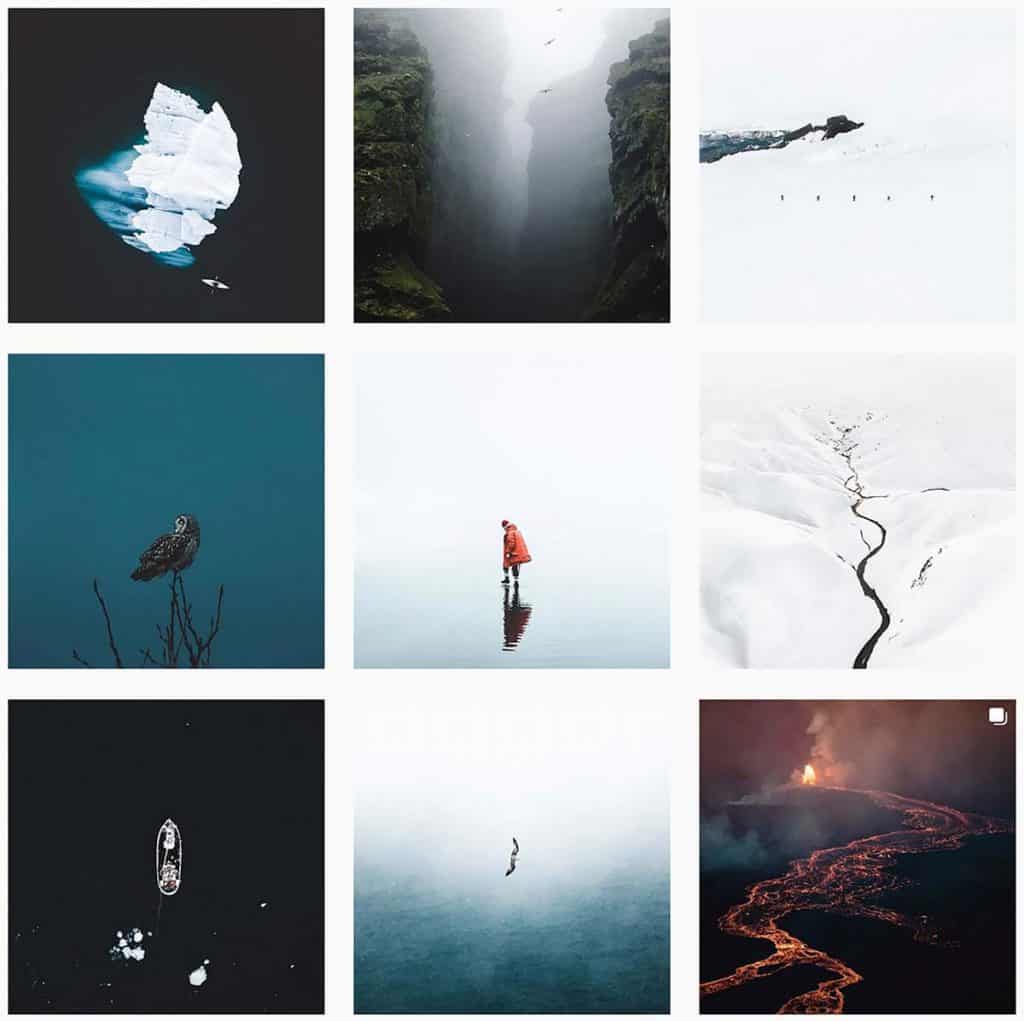

Space can also be digital, such as with Instagram which lets viewers look at your page in grid view where a website may show images isolated. This may mean you alter your sequence on Instagram to appeal to aesthetics. For example, photographer Benjamin Hardman who has over 600K followers told us that he uses social media as a “timeless portfolio as opposed

to a day to day journal.” What’s important to Ben is how the images work visually together. “Perhaps I’ll have a summer image with a green mountain. I may have to wait until it’s surrounded by monochromatic images, snowy scenes. That green image could then slot into the grid so that it doesn’t clash with other colourful images.”

Presentation

Presentation techniques can be used to elevate the viewing experience, to heighten the viewers understanding of the work. A great way to do this is by making the experience immersive. For example, Olafur Eliasson’s 2019 exhibition at the Tate Modern included interactive installations that used light, sound, shadows and reflections. One room was filled with a flavoured mist to the point you could not see beyond 30cm in front of you. It was overwhelming. One of the themes of the work is sensory exploration, so the concept work itself goes hand-in-hand with the ways it is presented and the space it is presented in.

There are many ways to make your work immersive or multi-sensory. For example, artist Tanya Houghton’s project ‘A Migrants tale’ is a 2017 series of photographs about the concept of home and nostalgia, told through the language of food. To coincide with the launch of this exhibition, Tanya organised a food events series of lunches or supper clubs. These were meals for up to 20 people inspired by one of Tanya’s migrant subjects and their memories of food from home. Through this sensory technique, Tanya was able to go beyond showing her project through images and instead allow people to experience it, through taste.

Context

There are contextual ways in which you can enhance the curation of the work you are showing. The most explicit example of this is with photojournalism, where each image is almost always accompanied by a descriptive caption detailing the who, what, why, where and when. This additional information contextualises exactly what they are looking at, and provides the viewer with little room for misinterpretation.

At Alec Soth’s major retrospective to date at London’s Media Space, there was a small room at the end of the exhibition with a film on loop. It was not one of the core works in the show, instead it was a documentation of how Alec photographed one of the projects. The film sheds light on how immersive the experience of photographing this work was, something which would not have been immediately apparent from just looking at the work itself.

There are also less explicit ways of adding context, such as the common technique of guest essays found in photo-books. For example, Magnum photographer Alex Webb’s celebrated street photography book, Istanbul, leads with an essay written Orhan Pamuk. The essay is not about Webb’s work, but rather about Istanbul, the place, the smells, the culture, the history. It sets the scene for the work that follows, ultimately enhancing the curatorial experience.

Other contextual things to consider may be the decision to show prices if the work is for sale, the time of the year you show the work if that has some contextual relationship with the content of the work, and whether an exhibition catalogue is required.

Working with a professional curator can help you express your ideas coherently, in the same way a musician works with a producer or a writer works with an editor. Just the act of having to explain your process to someone else will help you to see where the ideas could be expanded, streamlined, or made more, or less, explicit. It doesn’t have to be a professional curator that you work with. If you are not at that stage of your career then an objective person with arts experience would be useful. For example a friend, colleague or someone you admire with a similar career standing on social media. Don’t be shy, ask people for feedback and input. Most people will be flattered with the request and will be ready to help as a result.

This exercise is not for them to necessarily override your ideas, it’s a two way process. They could just be a sounding board or could be more active in the process. I think that is very much down to you, the way you work but also again, the nature of your work.

What this chapter has shown us is that curating your work is a creative process and can be as important as making the work itself, as it brings everything to life for the viewer. This is even more important in the age of everything being available digitally.

However you curate your work, good curation helps to contextualise what you are showing for the viewer. Whilst an in- depth exploration of curation is beyond the scope of this book, there have been some fascinating books written about this subject such as Ways of Curating by Hans Ulrich Obrist or Curation by Michael Bhaskar and we advise you to read more.