Before you jump into the podcast, we have something for you! We have created a content package proven to improve your art sales. Subscribe here to get it sent direct to your inbox right now!

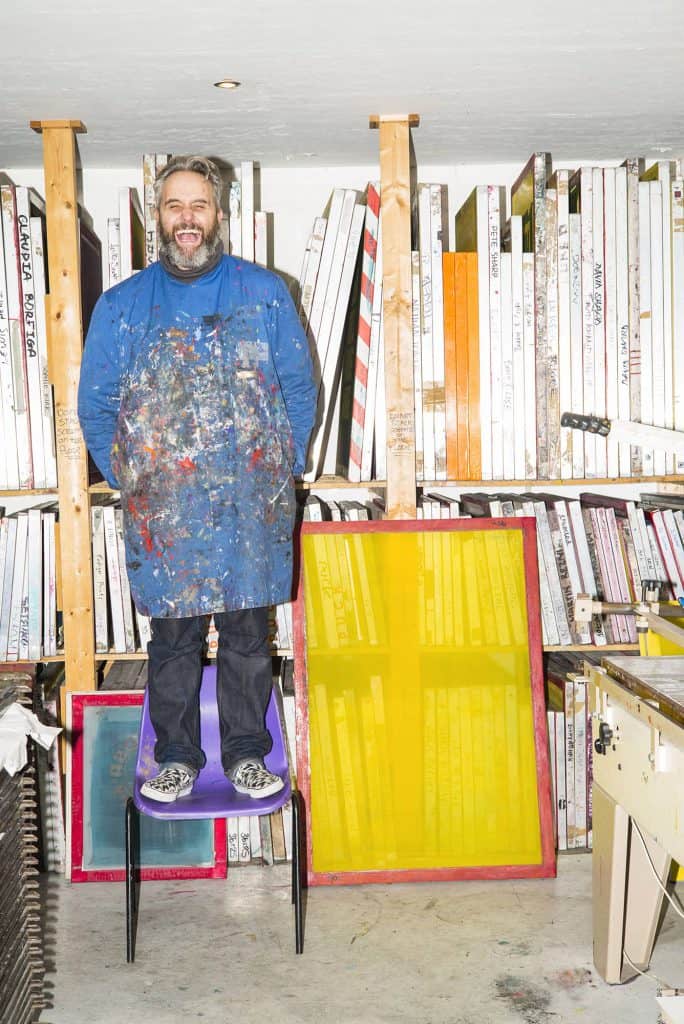

Dave Buonaguidi is a rare breed of person. He co-founded not one, but two legendary London based ad agencies and then realised his true calling in life was to be an artist, and he’s made a successful career out of that too.

Our latest Sell Out podcast episode is an insightful conversation between Dave Buonaguidi and Stuart Waplington, on the power of brand building for artists and thinking commercially about your art. It is packed full of the best bits of advice from Dave’s 30 years of illustrious experience as an advertising expert.

It’s rare to find somebody with so much cross domain knowledge in advertising and art. We have learned so much from his talk, so please listen and enjoy. And if you like the podcast, please share it with your friends.

Listen to this episode with Dave wherever you get your podcasts:

Transcript

Stuart: Welcome Dave to the podcast and thanks for joining us today. I just wanted to start by picking up on some of your early career. You had an amazing career in advertising before becoming an artist. You founded both St. Luke’s and Karmarama, which are legendary in their own ways as agencies in the UK. For people that don’t know St. Luke’s, it was a really unique idea, which was the first cooperative ad agency and no one was in charge. And I remember seeing this documentary about it, which I’ve just watched again this morning, thanks to you, and it was a fascinating idea ahead of its time. Now certain companies in Silicon Valley are picking up some of the ideas behind that.

Do you wanna tell me a bit about how St. Luke’s came about and what was the idea behind it?

Dave: Yeah, it stems back from, I think, probably going back to my parents who were both immigrants. My dad’s Italian, my mum’s Danish, they came over in the late 50s-60s. And I think when you’ve got that immigrant thing, you know that you have to do something a little bit different to survive. And so when I went into advertising which is the most traditional, old fashioned, white middle-class male business you can ever imagine bar politics probably. It’s still run exactly the same way as it’s always been run. The agencies, companies are all named after the three or four white men that own. There’s been a little bit of a shift more recently with people setting up interesting names. The name sometimes dictates how big a wanker you are. Basically, if you name it after yourself, you’re a twat. When you’ve got a name like Buonaguidi, and the bloke I was working with was called Ramchandani. He’s Indian. There was also a girl called Zamboni. When we were all working together, there was no way that we were gonna name the business we had after three, let alone five of the people who were in management at the time.

And so I’d worked in pretty traditional ad agencies all my career. I’d gotten a sniff of working in a couple of very good startups, one called Howell Henry back in the late 80s, that ended up becoming Agency of the Decade, which was just an amazing agency that basically broke the mould of the way that agencies could work with clients and the amount of work and the kind of work they could do. I was hugely influenced by that. And then I worked in big agencies, multinationals, and then when I had a chance to set up our own one, it was just one of those perfect storm scenarios. So I was working with this guy, Naresh. We were both working at an agency called Chiat/Day, which is an American agency. We found out after about two years of working together where we’d effectively started to rebuild what was a very dysfunctional agency office in London. They were huge in LA, New York and Toronto. I think that they had nothing else in Europe, and so they never came over to visit us. They just left us alone and we just started to build it, dismantle it, take it all apart, and try and build something that was a little bit more weatherproofed for the kind of modern era. And having had lots of influence from places like Howell Henry, which are pretty forward thinking agencies, we just took a lot of our experience in learning and applied it to somebody else’s agency effectively.

And then we found out one evening, I think it was a Sunday night, we found out that they’d been sold worldwide and effectively we were gonna lose our job. So we had a couple of options, which was the six people who were the management team could break up completely, and two or three of us would run off and get jobs elsewhere or set up another agency, or six of us could go and set up another agency, or we could take some clients or some people, and we made this decision. Actually it was a guy called David Abraham who’s now got his own agency. He’s a great, really clever guy. He basically said, Listen, it doesn’t make any sense to make this deal work with TBWA, who had basically acquired us. Everybody loses their jobs, all the clients get, they have to break up and pitch, and it’s very disruptive. And we made an agreement. Why don’t we fucking leave the deal and go and do our own thing? Take all the staff, all the clients. And it was massively exciting. Chiat/Day got hugely annoyed because they were perceived as the pirates. So the London office was out piloting the main pirate ship and they didn’t like it.

But eventually we put the deal to the people at Omnicom, who bought us, and they said, seems like a good idea. You can basically buy yourself out of the deal. We found an old empty toffee factory. We got a 10 year deal and it was free for two years. And we just moved the whole lot: agents, all the people, all the staff, all the equipment in there. It was massively exciting. But the minute you do something like that, you have to change the dynamic, you have to come up with something new. And so we didn’t name it after the five or six people, cause all our names were stupid. I was tasked with finding the name for it. And at the time, we loved working with clients who were a bit broken and they’d come to us and we had a history of fixing them and then turning them around. So brand turnaround was a big thing and it was something that we were starting to stand for in a way. And I think I discovered that the patron saint of doctors and artists was a guy called St. Luke. And so we just went, we fixed things with creativity and it just made sense. So we named it St. Luke’s.

Everyone thought we were a bunch of moonies and idiots and laughed at us. But it was interesting. I think you called it an exercise and an experiment, and I think it was very interesting to do it. I was 28-29 at the time, so I didn’t know shit from sugar. Don’t you just come up with these things and you think I would rather try something and make it different than do what everybody else is doing? And like I said, there were a whole load of things that forced us to do it the way we did and I’m glad we did it. And it was a fascinating thing to do. I learned a huge amount about people. I learned a huge amount about myself and the career I was in and the business I was in. I’m glad somebody did it and I’m glad, in a way, if somebody did it, I’m glad we did it.

Stuart: What was it like working out? We’ll put the documentary link in the show notes if anyone wants to watch it, but it was somewhere where you could decide your own job, decide your own salary.

Dave: It was a lot of that. A lot of that was sugar talk. There were still very defined roles. Me and Naresh were the correct directors. We had final say on the work. Andy Law was the chairman. David Abraham was the CEO. John Grant was head of planning. They would make decisions. It was still exactly the same as when we were a traditional agency. I think there was a lot of bullshit, just to try and make it sound a little bit sexier.

To be quite honest, the main structural change was everyone was an equal shareholder. So whether you are Rose, the cleaner, Roddie, the handyman, or mail man used to work. There was a shit he had. He ran the kitchen there. We all had the same shares but we all paid different salaries because we had different jobs and different job responsibilities. There was a thing called the Quest, which was sort of almost like the company barometer for the kind of decisions that we’d make about benefits for people. I remember when we set it up, we said we have to have the best maternity paternity healthcare policies and we have to be bigger and better than everybody else. And it’s pretty easy because at the time, advertising was pretty corrupt in every way. There weren’t very nice people. The businesses were run and governed by white middle class men who tend to be the most appalling people historically ever. And so there were lots of things that we could do overnight that would challenge and make it better for everybody else.

One of the issues that I think we found was that suddenly when you open up the doors to decision making and conversation to everybody, it becomes a bit of a free for all. And you end up with this kind of animal farm mentality where everyone thinks they have a right to steam in and get involved. And I think the thing that I really took from it was, it’s great to rewrite the rules but do it with caution because there were a whole lot of things that we rubbed out immediately. Old archaic formulas and systems that were just completely pointless. But when you try and when you flip it completely, you discover a whole bunch of things that you have no experience about how to handle and how to handle people who jump out their boxes and start screaming, yelling, and they’re on a placement and they think they’re the MD cuz you’ve said it in a meeting and it became quite difficult because you’d say these big things and then you’d have to constantly have the asterisks and the legals of it. Now actually when we said, you can pay yourself what you think you’re worth, that didn’t work like that. You were still paid what you should have been paid anywhere else. So there was quite a lot of bullshit involved. But for all intents and purposes, it was a much more free, a much more liberating experience.

My thing, and Naresh’s thing, that’s from the two creative sides, was we wanted to create something that was different, innovative, would break all of the old historical moulds, but also just be a great place to work for clients and for staff, because agencies aren’t, you know, big corporations as we now know, are not nice places to work. And I wanted to feel safe and I wanted to feel inspired and I wanted to feel relaxed so that I could do the one thing that I was employed to do, which was to come up with ideas for other people. And we wanted our clients to look at us and think they’re an inspiring bunch and we should pay them fairly and all that kind. I mean, we did stuff like when we had a budget and we underspent, we’d give that money back to the client. No business does that, let alone an ad agency. Ad agencies would be like, how do we get as much money for doing as little as possible out there?

There was a lot of morality, which I think is the one thing that if morality crept into the business in any way at all, that would be a really nice legacy to be part of. And I think all business now is becoming much more, female is the wrong word, but much more missionary rather than mercenary. And there are values and integrities that we didn’t have in the business, in any business, 30 years ago that are now completely commonplace and that’s how people make decisions about who they wanna work for.

Stuart: Completely agree with that. And how do you see the parallels between commercial creativity with advertising and art?

Because I think that sometimes when advertising is really done right, it has the power to really change things. Thinking of maybe Nike stuff with Colin Kaepernick and I was thinking about this in preparation for this podcast and remembering a great Heineken ad from a Scottish working men’s club where this guy and his dad are playing pool. It’s smoky like a working men’s club and his dad’s about to take a shot and he says, by the way, dad, I’m gay. And he says, Ah, no worries son. It’s the 90s after all. Things like that were like quite leading things at the time and pushing boundaries and stuff. So I think when advertising is done, it is an incredible art form. Do you see a lot of parallels with what you’re doing now in terms of the art?

Dave: That’s why I got into it. I’m probably not sure I chose it. I think I fell into it. I was really into graphics and drawing and painting when I was a kid. It was all triggered by my Italian grandmother giving me an old book, which I’ve still got. I’ve got it in here actually, which was one of these encyclopaedias of the Second World War. And one of the volumes was all about propaganda. And I loved looking at the images and seeing these three word headlines about recruitment or don’t talk. And it was pretty powerful stuff cuz if you did something wrong in those days, it was pretty catastrophic. And I just loved the way that they could caricature world leaders and there was something about the emotion of when you saw a poster with Hitler or Churchill or Mussolini or the Japanese soldier fighting the American.

There was something very powerful about that and so I loved it. I got into advertising by fluke really. I went to art school and did graphics and then fell into advertising. But there was something really interesting about the power of language, about the power of images and the power of also getting you to react in some way, because that’s all I wanted in advertising is you’d react and either buy something or stop doing something or start doing something. So they were pretty simple. Then there became this thing as advertising became more powerful and it was much more competitive and the quality of people coming into the business to try and get you to make those reactions was much more scientific. It became about just trying to get a reaction out of people. How do you remember that piece of thing that you’ve just seen or that you’ve just watched on TV or you’ve just driven past on the moment where you’ve heard on the radio? And so that meant you had to try a bit harder.

I think the examples you used, like Heineken. It’s a beer. It’s a lifestyle brand. They couldn’t even talk about the beer because it was illegal. So you’d have to try and set up this universe where you could talk about other things. Nike is not a brand, it’s a political movement. The things that they would talk about, the three words, the most powerful and the most evocative end line of all time. And there’s something about that power that I used to love. I think now the business has become a little bit more formulaic. I think we are much more reliant on data and that kind of shoot from the hip creativity has all been boiled away from what the business needs and what the business is good at.

I think in the old days, in the 80s and the 90s, you’d strive to create an eight or a nine out of 10. Now I think everybody’s quite happy with a three out of 10 is perfectly good enough and that’s why the work is sort of dog shit. And nobody seems to wanna push hard. Maybe there are people pushing on, it is a bit unfair. But I think it requires clients who are brave and who see their brand as a lighthouse brand that’s gonna change things and make things better, and make things interesting. And an awful lot of brands aren’t like that and as a result, the chain of suppliers becomes a little bit less interested and a little bit more fearful of losing the account and losing money rather than doing something that’s gonna change the world. And I would apply that to the art world as well. I think the reason I got excited about becoming an artist, and it was again, a bit of a fluke, was just, so often art can be quite passive. It’s like one of those things that you look at and you stroke your chin and you contemplate it. Whereas I’ve come from that world where Jamie Reid was making album covers for the pistols, and it was all bright and loud and sometimes offensive and would do stuff that would kick you up the ass a little bit. All of that propaganda, all of that 80s album covers, 70s album covers, the graphic nature of those images that had to try and capture or revoke a kind of a moment with just one picture in three words. I just try to apply that to art in the same way and it’s fun for me, but it’s also cuz it’s familiar.

Stuart: Because I worked in advertising production for a while and one thing, looking at that documentary again, that reminded me about something was where you guys would go in with an idea and the client would just say no and you thought it was the best idea ever. And probably the thing that you were proudest of was always the thing that they pushed back against. And is it refreshing now to be on the outside where you don’t really have that kind of restriction?

Dave: It’s amazing. It’s amazing. But I tell you what, I was just talking to somebody earlier about it. When I worked in advertising, one of the things that drove me mad, and I think it was the turning point for me, was that when I was at Karmarama and just the amount of wastage and everything about the creativity, ideas, time, money, it was just appalling. And I remember thinking, Look, we’re not stupid. We’ve got some good people here. We sit down with a client, we agree on a brief, and then we go off and come up with ideas that should be on that brief and then why is that work not going through the first time? We did a bit of analysis, and this is gonna sound really boring, but obviously it was driving me mad and I said, Look, can we just do a bit of analysis and try and find out how much work goes through the first time, first presentation?

It was 0.03% of the work we did. And we were doing like a thousand ads a year. 0.03% of the work goes through the first time, so you’d end up having to have six meetings to get the work done. And it was because a lot of the time there are a whole bunch of agendas. The minute you get six people in a room with a notepad each and a pen, the agendas are all there. So the client wants something that’s gonna help him get his summer bonus and get his Christmas bonus. The agency creative wants to do something that’s gonna win them an award. The MD wants to get a piece of work, or the managing director, or the head of client services wants to do a piece of work that’s not gonna fuck the client off that he leaves, but is also gonna keep the creatives happy. So it’s like a Muzak that’s created. Somebody likes rock, somebody wants classical. We’re not in a rock hotel, we’re not in a class. Why don’t we just create Muzak, which is this horrible vanilla bullshit that everybody can not hate. That’s the problem. And it’s not about liking or loving anymore. The odds are too finally stacked against you.

I remember working with a guy called Jay Chiat, who was the founder of Chiat/Day, and he was a big collector of Damien Hirst very early on. And I remember talking to him about one of the pieces he bought, and I think he bought the piece, which was a cow’s head that was rotting, and there were a whole load of flies that would chew on it. And then he had one of those big electrical zappers, and it was just life, the cycle of life or whatever it’s called. And I was so surprised at him and he just said, No, because Dave, my day job, I have to do one piece of work that a million people love. And he said, For my collecting work, I buy one thing that only one person in the world would love. If you showed that art to anybody, to a thousand people, 999 of them would reject it. He said, I’ll buy it. And I love that thing of flipping it. Using all of that science and information and data mining and all of the insights that we have in creativity that we apply to making hopefully the right decision.

When you’re your own client, fucking only do whatever you like. I think when I worked at Karmarama last year, we worked out that we would do a hundred ads, a hundred ideas to get one. Now, if you can imagine presenting a hundred ideas to 50 people who are all part of the decision making process, the kind of work that’s gonna get through a hundred people or 50 people is gonna be the most vanilla you’re gonna ever imagine. And so that idea of I, as a creative, wanna do something that’s gonna challenge and be brilliant. I don’t give a fuck about awards. I’ve never entered them. But it was like, I want to do something that makes me feel good. Or is it that’s gonna challenge the status quo and make it better? No one’s interested, No one gives a fuck about that. All they wanna do is just get something that’s quick on budget. And sort of ticks 5 outta 55 boxes that need ticking. And everybody could agree it is the least defensive bit of work. And as a result, you just end up with the bullshit we’ve got.

Whereas wasting 99 ideas and the time it takes to come up and the stress it takes to come up with those ideas in order to make the shittest idea that you’ve then got to spend the next year making, by the time you’ve finished it, all you wanna do is hang yourself. And you’ve been there. You had been in production, you would’ve been there. It’s just appalling. And human nature dictates that it’s gonna be great. It’s gonna be amazing. We’re gonna look back. And then you look at it when you present it to the rest of the agency, you go, fuck it now, what am I doing? And I think that’s the turning point for me, was when I just realised the odds weren’t gonna get any better. The work wasn’t gonna get any better, and I needed to do something that could help me do some of the things that I really still love doing, which is coming up with ideas and then making them happen, and then engaging with an audience. And so what I do as an artist is not really that different from what I did when I was working in advertising, but it’s just there’s one client, me. I get to say, would you reckon? Should we do it? And then I do it.

Stuart: Is there any kind of feedback that you take into account as an artist?

Dave: Yeah, I do. I try to work very closely with the galleries that I sell through. I still like having feedback. I’ve come up with probably 20,000 ideas in advertising of which I’ve probably made about a thousand. So I’ve had plenty of knock backs. I’ve been married, I’m divorced. I’ve got plenty of scars and broken bones that I’ve recovered from so I don’t cry anymore when people don’t like my work. It really doesn’t bother me. I just respond, listen to it. If I think they are assholes, I’ll ignore them, and if I think they’re right, I’ll do something about it. And I really enjoy that process. I love working with galleries and talking about shows that I wanna do with them and talk about new additions of work that I’m doing. I love doing that. I know a lot of people find that quite uncomfortable. I suppose it helps that I’ve got the experience I’ve got and I’m as old as 58. If I was 30, I’d probably struggle with it. If I was in my 20s, probably even more, because you’re much more precious. But I’ve also got a big dollop of discipline in what my brand is. This is gonna sound really wanky, but what I call my brand universe, what my colours are, what my vibe is, what my language is, what my font is. All of that stuff is something that was second nature to me when I was working on Ikea or Costa Coffee or whatever it might be.

So applying that to myself is a good discipline to have so that when I come up with a new idea, I can go, that’s the kind of stuff I do. This isn’t the kind of stuff, I don’t do it. If you really like it, work out a way of retrofitting and making, if you put pink in it, it might be enough. And so I’d still apply that kind of logic to it, and that really helps.

Stuart: Yeah, and that was something that was really interesting to me to ask you, that sort of knowledge you have of that kind of consistency of brand, is that something really important for an artist?

Dave: Personally, I think it is, and hopefully there’s gonna be a lot of different artists who are gonna look at this or will listen to this and will disagree. I think it can be predetermined by your age, the kind of work that you like doing, your experience, your personality. I’m very commercial. I have no shame in being commercial. I know I’ve gotta make money cuz my kids go to nice schools and I’ve gotta pay off my ex-wife. So I’m disciplined enough to know that I have to run it like a business. I come in every day at 8:30. I go home every night at 8:30. I do what I’ve gotta do and I make a shit ton of stuff that I try to sell.

I think a lot of people have got elements of shame about what they do and if I make money or there’s a huge contradiction at the heart of it, which is, I’d say being an artist is the second best job in the world. The first is being a model where you don’t even have to fucking try, you literally turn up and get your bum out, male or female, and somebody pays you quite a lot of money to put their clothes on and then you can do whatever you like. It’s real zero effort. As an artist, to be able to sell something that you love doing, that you find really easy, to people who like it so much that they will give you their money, it is just an amazing feeling. I think in this country we are slightly ashamed of making money, whereas in the States we don’t have a problem with it at all. And so a big part of it is coming to grips with whether you see this thing as a side hustle and that’s the bit that you do because you love doing it, but you don’t mind not making any money cuz you’re making loads of money being an arms dealer, drug dealer or working in a bank or working in advertising.

I would say that you are kidding yourself. And one of the things I learned in the experience that I’ve had over the last few years, removing all toxins from my life, is the most liberating thing you can do. The minute you release yourself from all that bullshit and that stress and pain, you find yourself swimming in much more calm waters, and it is a beautiful thing. And making money and making good money doing something that you love doing, there is no better feeling. And so I would absolutely encourage it. However, like I said, I’m 58 and I’ve got things that I need to pay for, so I don’t mind being commercial. There are plenty of other artists out there who are quite happy to paint dead bird’s heads in with oil paint and all that kind of stuff, and know for sure that it’s not commercial and maybe they play a different game. They play the long game. If you’re in your 30s, you can maybe afford to do that. It’s a little bit more hit and miss. I’m in my 50s. I’ve got maybe 13, 15 summers left before I’m either put in a box or I’m gonna be farmed out into a weird home cause I’ve been out in the street in my underpants again, shouting at people.

And so the way I look at it is I’m running outta time. And so I’ve come to terms with the fact that for me, it’s okay. For other people, it’s a different thing.

Stuart: I think that what we do is encourage everybody, every stage of their careers to actually think commercially because if you’re in your 20s or 30s, you probably want to create work all the time and you want to dedicate time. You don’t want to have that job in a bar or whatever it is, and just have to squeeze it around paying the rent.

It’s always strange to me how in visual arts, nobody talks about being commercial or like this sense that if you are too overtly commercial or you’re thinking commercially, it might impact negatively on your creativity or the purity of your creativity. Whereas, for example, if you take music: When people sell a lot, they get a gold disc and everyone claps and everyone’s happy.

Dave: It’s exactly the way to look at it. I mean, I don’t think there’s a difference between being an artist, being a musician, being a fashion designer, and being a filmmaker. Being a filmmaker, you have to deal with lots of people who have to engage with your work, and you have to deal with studios and actors and all that kinda shit. Being a musician, exactly the same. Being a fashion designer, exactly the same. Being an artist, you’re still dealing with customers, you’re still dealing with galleries, you’re still dealing with infrastructure. But the fact is, you are creating a product on your own. You’re creating a product that people like and that people want. And when you do that, you should be rewarded for it. And I think there is absolutely no shame.

Absolutely, think of it like music. It’s exactly the same. Some people like Radiohead who are different musicians to Take That or to One Direction. But at the end of the day, it’s about those people and what they like to do and the vibe that they create in the same way that Alexander McQueen is different to the bloke who created Ecstasy and the people who created Nike. They’re all effectively doing the same thing. They’ve just got different ways of stringing it. Absolutely, that’s one of the things, think like a business.

Think like you are a brand and then be fucking absolutely professional about everything that you do. Because for me, it’s the best job I’ve ever had. The fact that I had to wait until I was 55 before I actually discovered what the best job I ever had. I just felt like a fraud before and I felt like I was lying to myself. I thought I was acting. The daily struggle of trying to get through the day being surrounded by shitheads and wankers who were all trying to fuck me over. And I just found it exhausting. Whereas now, I realise I’m more studio than I am boardroom. I don’t like wearing colours. I like being covered in ink and I’ve found my place and I’m very happy to have found it. But I think for a lot of people, embrace what you are but then be professional. Treat it like a business because it is a business. If you do it right, it can be a very good business and there’s no shame in that.

Stuart: And unless you are independently wealthy, then you wanna be doing it all the time. You’re gonna have to find a way of paying for it. And if people buy your work, then you know, they have it on their wall. It inspires them. It has to be like a strategy to get people to buy into your work and to actually make that decision to purchase it.

Dave: Yeah. You have to stand for something as well. In the same way that you will buy an iPhone instead of a Samsung for whatever reason. You will buy a VW instead of a BMW for whatever reason. We make decisions about the brands that we interact with. You watch Channel 4 as opposed to ITV for whatever reason. All of these things are driven by brand connection and brand values. You want like-minded brands to be in your life. Same way that you do with music, same way that people turn around and go, Oh, I can’t wait for the new Tarantino movie. Whatever it is, I know it’s gonna be good.And I think with artists, you have to be in that position where you stand for something or you mean something to people. The great thing about all the great artists that we could ever name, you could put all of their work in a room for a thousand other pieces of work by other people and you’d be able to spot which one those people did. And that’s a great discipline to be in and to have when you’re creating work. How do I stand out? How do I mean something to people? How do I create a brand connection or an emotional connection to my customers or to other people? I’m quite happy being pop music I want. My dream would be if everybody on Earth bought one of my pieces of work, I’d be ecstatic. If they got two, I’d be even happier. But to be honest, I want people to like my work. I’m not interested in people going, yeah, no, I don’t care. I want people to like it and that’s what drives me.

Stuart: We were talking about your brand as an artist and artist having a brand, like for example, your brand I see it’s this sort of positive message running throughout it. Very upbeat. And your brand as an artist, is that the aesthetics? Is it the message? Is it the medium or is it some kind of combination of the three? And is it something you consciously think about, or is it something that just emerges as you do it?

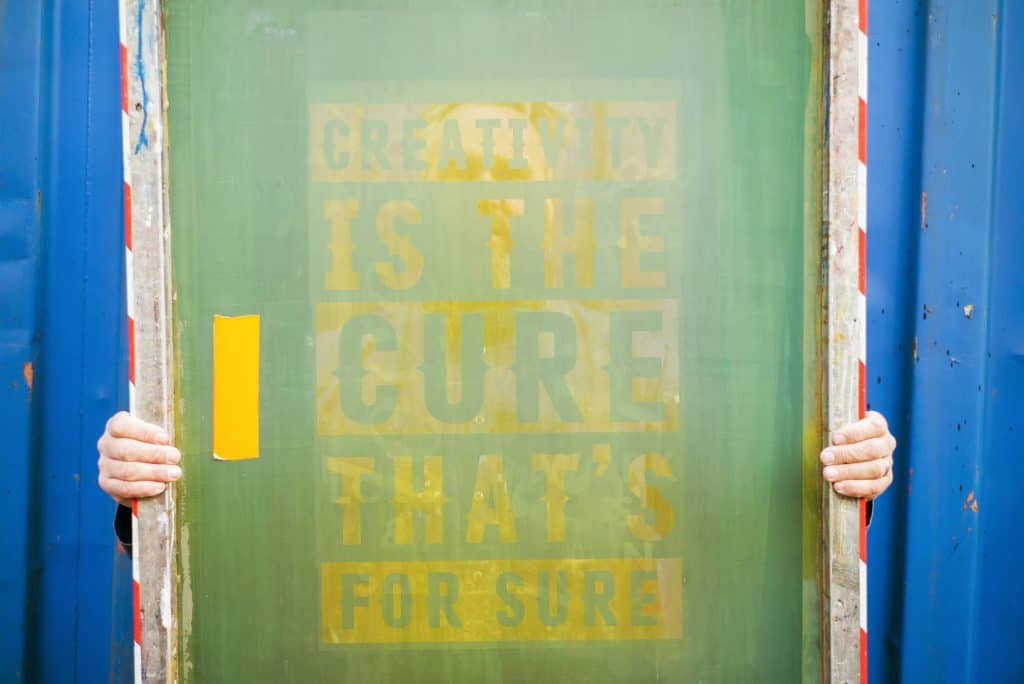

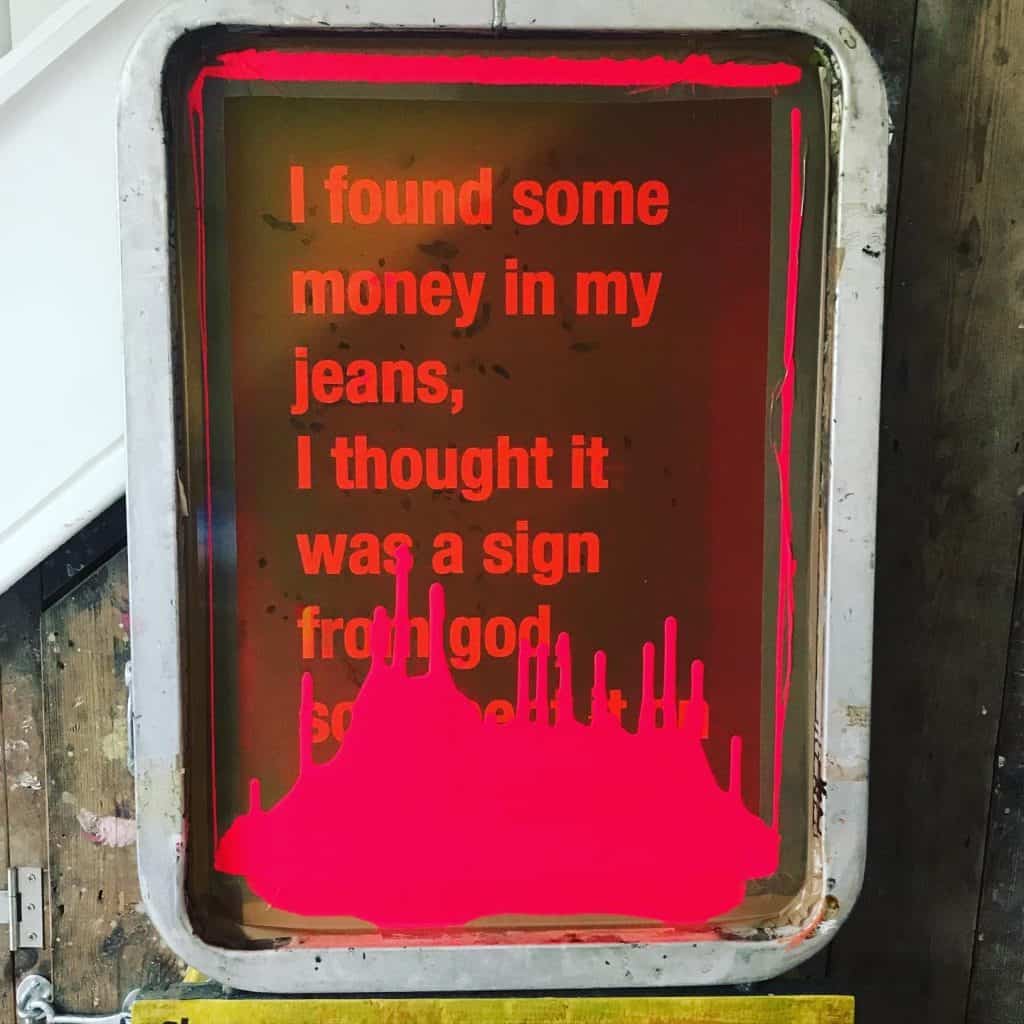

Dave: It’s a combination of all three. And it is something that when I first started doing it, because screen printing and being an artist, there is a lot of technical stuff in it and I didn’t really know what I was doing. I loved the process. I loved the very analog nature of, you know, creating an image on a computer, printing it out onto an acetate, exposing that, and then printing it. I love that. But also for me, screen printing, there’s something about it that reminds me of advertising in a way. It’s like mass production. Now I can make hundreds of these if I want to. The thing with, what was the question again?

Stuart: I was wondering if your brand just emerges over time or whether it’s something you have to consciously think about.

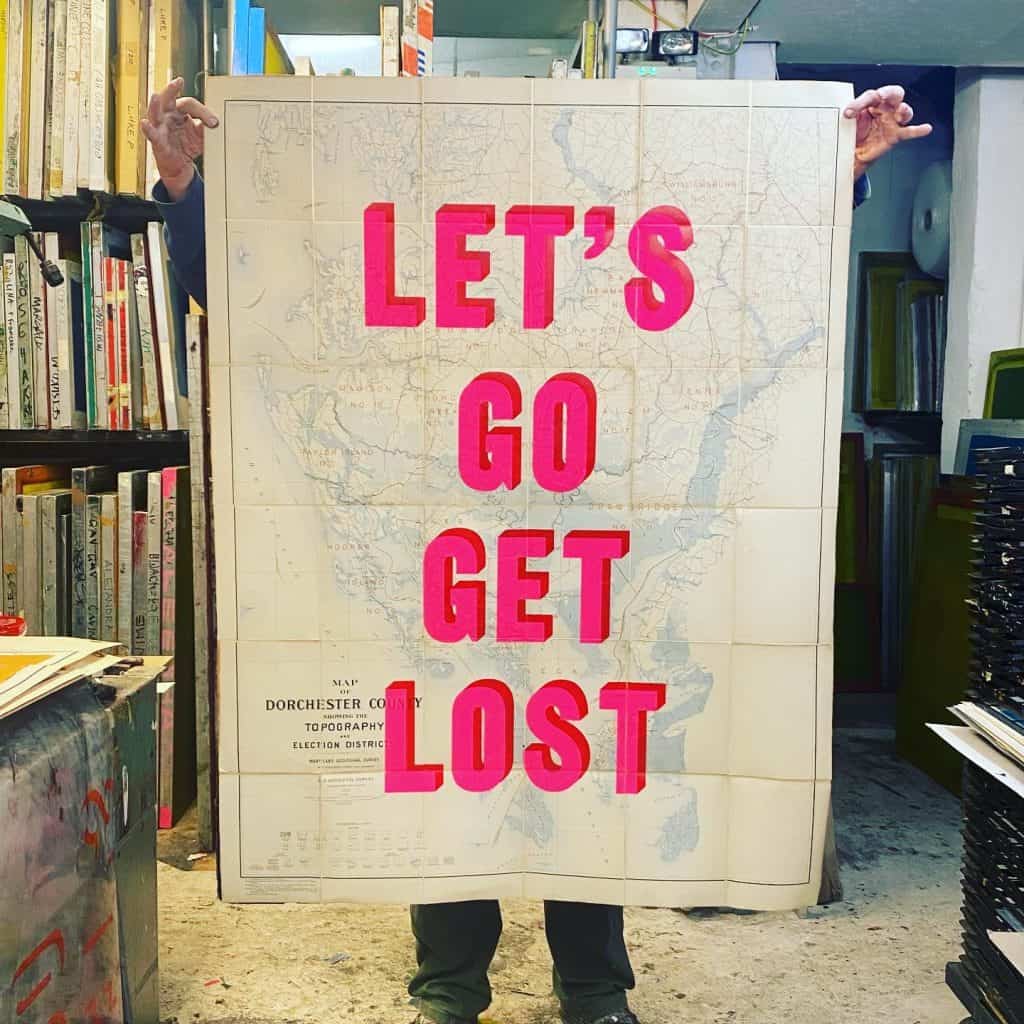

Dave: Yeah, so learning all the technical stuff was a big challenge because it is something that you can learn and you get better at it. I think creating that brand thing, and it was, I remember there was a turning point for me, I was possessed by recycling and upcycling. I’ve always done it. Seeing something in the street and thinking, Oh, that would make a really good, I don’t know, I’ll just go and get it and do it, turn it into a clock or do something. So I’ve always had that in my DNA. With the screen printing, finding things like the maps and finding things like the pink were things that happen pretty much at the same time. How do I make it stand out, make it pink?

Finding interesting things that are already highly emotive, like a map. You put a map on a table in a full room, everybody within minutes will be looking at it, trying to work out where it is, what’s the connection that they have. They’re also beautiful bits of work and they’re also completely obsolete because now I’ve got an annoying voice on my app, on my phone telling me, turn left, turn right, go up to the next right and take the second exit. Whereas these things were created by real artists, they are completely pointless. You could probably remember your dad sitting in the howling wind outside of the A3 trying to get from Guildford to London thinking, how the fuck am I gonna do this while the map’s blown around? It’s impossible.

But I think there’s something beautiful about those things. And so for me to take those and then do something with them. But the turning point I think was art is very dry. A lot of art is very dry. And I came up with this phrase a while ago that I told somebody and they just laughed at, they said, you’re an idiot, it was lull art. And it was in the same way as pop art. It’s like doing stuff that gets a reaction. I like making stuff that makes people laugh. And graffiti is often there to make people angry or to get people to do things. And whereas the stuff I like doing is just stuff that makes you feel good. But I know that if I ever do Live Love Laugh, I’ll hang myself. You know? If I ever end up with a piece of work and I’ll get a bonus, I would be really disappointed. And there’s a lot of people who do that, and there’s a lot of people who are very successful at doing that. So my thing is, okay, I wanna make people laugh and I wanna create a reaction, but I then have to do it in my own way.

And that’s the thing that creates the discipline of you go, I don’t know. So you use slang or you use stupid words, or you use things that don’t make any sense. And I like that kind of randomness of trying stuff that stops it making sense. When you hear stories about David Bowie writing lyrics by chopping ’em all up and sticking ’em all together again, there’s a kind of craziness that I just think is brilliant. And he owns that. It’s not pop music. He’s still massively successful. He creates amazing music. But he did it by applying a technique that broke it all up. And I like doing that. I like doing stuff that doesn’t really make any sense and then if it’s pink or if it’s on a map or if it’s on some other bit of found ephemera, then it feels like it could be mine.

Stuart: So do you ever come up with an idea that you think, I’d love to do that, but then you have to modify it in some way to fit with your brand?

Dave: Absolutely. Classic example was you look at the sort of Robert Indiana LOVE, right? The famous LOVE image, which is the greatest, probably that and I Love New York. If I could have ever done two things in my life, that would be it. You look at it, everybody’s done their version of it. Everybody’s ripped it off. I was sitting there thinking I’d really got to do something with love, but how do I do something that stands out, that’s different to what everybody else is doing? And I stumbled upon this thing completely by fluke. Somebody showed me a picture of the tail end of a massive bomb that they saw at a flea market. I told him to get the bloke at his stall, let me buy it. I bought it, ended up being a meter and a half high, the tail section of a thousand pound bomb. After a long period of looking, I found the top end, which is the business end, which is the bit that’s got all the nasty stuff in it. The only one I could find had cement in it and it weighed a ton and was the kind of thing that they would strap to a Harrier jump jet in the 80s as ballast as a weight thing. So that when it was flying on maneuvers, they would give an idea of roughly how heavy this bomb was.

I think I turned it into this big eight and a half foot. I dunno whether it’s a statue or a thing. Got my mate to spray it gold, printed LOVE on it. So it’s just called love bomb. But it was a really interesting thing for me that I don’t wanna do a print with love on it. I’d wanna do something different and tell a little bit more as a story. So I made this great big bomb. I did loads of hand grenades as well that were quite cute and gold leaf and gold plated. And it was a nice thing to have in my head. I knew I was gonna do something with love. I didn’t know what it was gonna be, but when it sits in the creative mind, it’s always sitting there. And the way I look at it is, it’s like having loads of flies on the inside of your head. And then suddenly when you see that bit of fruit that you think, Oh, that’s an opportunity, that fly will go to it, land on it, and you can then make it. And so having that sort of discipline, but also that looseness to try and find those things that I wanna make a bomb with love on it. How do I make it look like it’s mine? It’s easy cuz pink and gold and all that kind of stuff.

Now, last year I had another idea to do a thing called Killing Me Softly, which was to rebuild an electric chair and in the seat have a pink seat, the base, and a pink seat at the back, and then a cap. And what it would do is it when you sat in, it would just massage your buttocks and your back. And I thought taking something like an old found object, which I do with maps and I do with bombs and all sorts of things, and then trying to apply something different to it could be quite good fun. I just couldn’t make the fucking thing work because every time I said I’m gonna get an electric chair, the first reaction by everybody was like, Oh God, really? Whereas when I talked about the bomb, I dunno. Even though they effectively do the same thing, they kill people. And there’s something really weird about the manufacturing of an object, like a handgun or a bomb or an electric chair that’s manufactured by people and has a creative director going, can you just slant the legs back a little bit and make it look a little bit nicer?

There’s something really weird about that. But I just couldn’t make the electric chair thing work. And maybe if I ever become famous one day I might just do it, but at the minute, I don’t want to do anything that makes people angry. And I think it’s a very volatile thing.

Stuart: That kind of something that you learn as a creative director in advertising, that you’d have all these ideas swelling around your head and you’d have to wait for the right client to go, that’s right for you. And so you’re kinda doing that in a way yourself. You’ve got all these ideas swelling around and waiting for them to coalesce into something that sort of fits with what you stand for.

Dave: And sometimes you’ve gotta do five bits of work. Like chess you’ve gotta do five moves ahead. It was a saying that we used to say in advertising, you’re only as good as the last ad you made. And I would apply that to being an artist as well. You’re only as good as the last piece of work you made. But thinking about: what your career path or what your thing is, what is it you want to achieve? I don’t really want to have, like I said, I’m late. I came to it late. I’ve got 13-15 years left. I don’t really have any ambitions to have a one man show at the Tate Modern, but I know I like doing shows and I know I like doing lots of work. And so I’ve got a career plan, which is every time I do a piece of work, how do I get people to like it? How do I get people to buy it? How do I get gallery owners to look at it and think, this guy’s good. How do I get conversations with other galleries to go, let’s do a show. One piece of work has to lead, has to create 10 opportunities.

And the great thing about your earlier point about when you come up with ideas, when you work in the corporate world, when they get shut down, they never see the light of day again. When you put ’em all in a drawer and think, I know what that idea with the cat and the dog who talk to each other and dance, I can use that for a multitude of things. More often than not, you won’t be able to, because so much creativity, it’s like custom built around a concept or an issue that you have to try and resolve. Whereas with art, you can come up with all of these ideas and then just work out how far down the conveyor belt you are gonna put that idea for you to make it. And sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t work. I mean, that’s the great thing. I’ve come up with so many ideas. I think, Oh, this is gonna be amazing and it is fucking absolute shit. And then other times you do something on a whim that you put together in 30 seconds and it could be the best you’ve done that week.

Stuart: How do you know when something is going to be something you wanna stick with and how quickly do you kill things? And what kind of feedback do you take to make that decision?

Dave: I ask and I talk to galleries a lot. Galleries take 50-60, sometimes even 60% of the money that they make from the sale and you’ve gotta ask yourself, okay, if you’re gonna give somebody half the money, you make sure they work for it. And so I like to every year go and have a meeting with all the gallery owners and say, let’s talk about all the finances and talk about how the business has gone and what I need to stop doing, what I need to do more of. But then also, every time I come up with: I’m doing a show with somebody, absolutely share that work and listen to them and get feedback and take it on board and try and work out how you can get better. You’ve gotta make sure that you can squeeze every bit of knowledge and every bit of insight out of what they do to enable you to become better at what you do. And it depends. Some people love to just operate on their own. Other people like to listen and need constant reaffirmation and conversation to help guide them. And that’s how I like to work.

Stuart: In your work in advertising, I guess one of the principal things, and you said this earlier, was how do you cut through the noise? How do you get attention to your work, whether it’s a commercial app piece or as an artist, when there’s so much other stuff out there and how do you get noticed? And that’s obviously something you’ve clearly achieved in your art career as well as your advertising career. So what kind of strategies do you use for that as an artist?

Dave: As an example: I remember when I was working at Karmarama in 2003, I was working with a guy called Scott Leonard and he said, Oh, there’s an anti-war march coming up. We should do something. And at the time, there were a few marches that had happened and it was always really dry and po-faced and we knew exactly what people were gonna do. They were gonna do: don’t attack the rack, and their blood on my hands. And it was all gonna be very po-faced and angry. People from the home counties who were gonna march down to London and complain about things cause that’s what they liked to do. And I remember we sat down and we just started having a laugh with it. And we came up with this idea of Make Tea Not War. And it was Tony Blair with a teacup on his head, holding a Kaashnikov machine gun with the most stupid comment you could imagine.

We were quite cautious about it because I remember at the time thinking, there’s gonna be a lot of people who were gonna die here. This is gonna be quite a big war that’s gonna go on for quite a few months. And that means lots of deaths. And you don’t wanna be flippant and disrespectful of the people who are gonna die. But also you have to have an opinion about whether it’s a good thing or a bad thing. The original idea was Why go to war when you can go to Wales, which was just a bit random, which just happens to be that Scott likes Wales. And so we settled on Make Tea Not War. We printed a hundred of them, we put ’em on sticks. Scott drove down to the march, handed ’em out to people, and I remember he just called me up in the morning and said, just go down the newsagent. And I remember it was on the front page of the Sunday Times and lots of the papers had it.

And it was this sort of moment when I thought, fuck now hold on, you can do something that’s quite pure and simple in its approach, but it can stand out. And that was complete fluke, complete luck. It easily could have disappeared off the face of the earth, but I think it was because it tried to do something different. Cause it wasn’t playing the same game as everybody else and doing really heartfelt and meaningful and quite dark and worthy messaging. It was stupid. And I look at marches now and I love looking at the posters that people have doing marches cause it feels like they’ve been released. They can say whatever they want and they’re really, really clever, Really cute. I remember my favourite one is, ‘I’m so mad I made a sign’ and it is not even commenting on what the march is, but I just love that the personality comes through. And that’s what felt like a moment for me because in advertising we’d always try to be a brand that had a personality, the agency, but you weren’t really allowed to. Whenever I did ads, you would always try and apply a personality of that brand to the work that you did. And as an artist I think you have to do the same and work out what your personality is.If you’re really straight and boring and you like colourful birds then do that. But if you are a bit more of a challenger and you like to make a bit of noise and you like having to laugh, then make sure that personality comes where you work. Because then it makes it remarkably easy to do stuff because you’re not trying too hard, you’re not acting. And so just applying that kind of logic has been really useful. Always just try and challenge what you think everybody else is doing and you’ll immediately stand out. It’s like when we named St. Luke’s, we could have named it like everybody else does, but the minute you’ve changed the name, it’s one of the most fundamental things that ever happened in that agency was not naming it the way that everybody else does. It was also the simplest thing we could have ever done. You think a little bit and plan something ahead, what could I do that’s gonna stand out?

Stuart: There’s lots of advice out there for artists, which is around strategies like, how often should you post on social networks? What should you be focused on? Email? Should you do this, should you do that? And some of it’s important, but I think what you are saying is you’ve gotta take it back to the idea first. Being great at knowing when to post stuff and how often and making videos and stuff like that, all of that’s also important because that is the channel, that’s the way you get it out there. But if you don’t actually have that personality and that sort of clear idea in the original thing you’re putting out there, is that kind of what you’re saying there?

Dave: Absolutely. But it’s also, when I worked in advertising, when you said something, when a client said something, it cost them a fuck of a lot of money. It would take them a year to make and it would cost them north of a million quid every time they did something. Just to put it on TV would cost them a million quid. So when you suddenly go, I’ve spent 10 million quid putting this thing together. Make sure it’s important. So then you have lots of very clever people all trying to put together something and you listen to a lot of people and you make sure that messaging is bang on right.

The problem is social media is completely free. Everybody can do it. I remember a guy coming in from Facebook and he was telling us about Instagram, saying, yeah, this is how you put together the perfect post. You only post at six in the morning or nine o’clock at night. And then when you do your post, have one clear picture that’s graphic and then leave a 12 line gap and then have all your hashtags. And I thought, mate, that just is Grammarly. Grammarly has created a sea of people who are too thick to be able to learn anything. So what they do, Grammarly makes ’em seem intelligent, which is a cheap, So if all of a sudden I’m getting loads of Instagram posts and people that are all applying the same logic and the same rules and helping them apply it there to be their optimum, it just means you’ve just created saturation of just everybody doing exactly the same thing.

I think again, be clear about your personality and make sure that your personality takes everything you do, you know? You don’t dress the way you dress because there’s a format that Facebook could put out and tell you how to dress for success. You wouldn’t do that. You dress the way you wanna fucking dress. And I think having social media approach in exactly the same way is really valid. I was talking to a guy, Tom Byng, who was the founder of Byron, talking about his Instagram feed, saying, why is it so boring? I said, mate, because all you do is you make burgers. So what you do is you talk about burgers and you talk about milkshakes and you talk about chicken. Now, the way I use my social media is I think of it like when I worked at Channel 4 and I think of it like a TV station. So it’s got drama, it’s got sexy, it’s got countdown, it’s got the news. Channel 4 isn’t one thing, it’s about a thousand different things, and that’s what makes it a really interesting brand. So when I do my feed, I wouldn’t by any stretch of the imagination say that what I do on my Instagram feed is good, but it works for me. And so sometimes I won’t post for two days. Other days I’ll do 12 posts in a day, depending on what’s happening. I’ll do everything from me commenting on things, me trying out stupid things, me eating things, me selling, talking about my work, talking about other people I know.

I just want when people look at my social feed, what and all to know who the fuck I am, and that works for me. You know what I was saying to Tom about the feed for Byron is when you talk about the chefs, talk about the inspiration for the sources, where it came from, the holiday that you went on that told you about that type of bread that you might wanna use. Still talk about burgers, but talk about the fucking blokes and the girls who make the burgers and the story that they had. Let them contribute. Because when I walk into Byron in the same way that when I walk into Wagamama or I walk into Wimpy or Honest Burgers, they’re all completely different experiences and they’re meant to be. They’re meant to stand out. So make the thing that you do unique. Why the fuck would you engage with Apple instead of Samsung? Could be a million different reasons. But it’s like making sure that you have a clear plan as to what you are doing and why you talk in a certain way and why you dress in a certain way and why you do that work in a certain way.

That’s what people will find attractive. That’s what people want from you, is they want your personality and so then use social media in the best way possible to get that personality across.

Stuart: You do a lot of exhibitions, you are active on social media as well, and you sell through your website. I became aware of your work, I think, for Jealous Gallery. You’ve been to a few shows with them and through Print Club as well, but then you’ve got your own store and then you’ve got your social media. What do you think contributes to your sales more or do you think you have to do all of those things?

And how do you choose not to do certain things? Do you try things and then it doesn’t work? So once you’ve got that message that you wanna say all the things you wanna say, how do you know what channels to use and that kind of stuff?

Dave: Yeah, it’s a good question. So sometimes going through a gallery is the right way, but sometimes selling it on your own is the right way of doing it. I think all of these things become more apparent as you get better and you become more experienced and as you start doing sales. When you have that hard conversation with yourself about, this is how much money I made last year, this is how much the galleries took off me, which is the same amount of money. It hurts. But also, galleries are really useful. Galleries will help you with exposure. They’ll help you with professionalism, they’ll help you with attitude and the way that you run your business. You can learn a lot from galleries. And so I would never wanna be in a position where I’m doing stuff without galleries. I really like the galleries I work with and we have a good relationship.

But also I like doing stuff for myself. And I love doing things like collaborations and sometimes when you do collabs it doesn’t work putting it through a gallery, cuz then you have to split everything three ways and you just become a bit of a charity and the collab will often start with two artists talking to each other and then the gallery just sells it and posts it. And they’re doing pretty well for not doing an awful lot. So I think it just depends on the piece of work, the work that you do, and also what the opportunity is. I love doing shows. I love having shows and obviously that only works with galleries. Interestingly, I’m renting a new studio in Hackney Wick, which is about twice as big as what I’ve got now. But I’m gonna be sharing a space with another artist. So we’ve got the same space, but upstairs we’ve got a gallery which somebody else will run. So it won’t be Real Hackney Dave or Dave Buonaguidi Gallery. It’ll be another gallery. But it means I can sell my work through that gallery and also put on shows.

So it suddenly becomes another aspect of what you can do if you want to. But again, think about it like a business, have a plan, have ambition about what you wanna do, what you want to achieve, and then fucking do the graft and fucking do it. I think we sit there with our hands out hoping it’s gonna happen. It won’t. You’ve just gotta put a fucking shift in and get it done.

Stuart: Yeah. And I think it’s easier these days to be able to do that, to be able to take control of your own career because there was this kind of thing, obviously pre-social media where you’d have to really go and convince a gallery in the most part to show your work. And now if that avenue’s not working for you, you can just go and take control of it directly and go and reach your own audience.

Dave: Galleries are, this is probably gonna get me into trouble, but they’re like vultures. If they see a body that’s still got meat on it, they’ll go down and get it. And so I remember working with quite a few galleries who wouldn’t touch me with a fucking barge pole when I first started cause I didn’t have any work. Then when I started getting my social media stories sorted out, when I started doing a little bit of advertising bullshit saying, I’ve done this campaign, I’ve done this new body of work, it’s all sold out. Sometimes I never did that. But it’s good to have a strategy as to whether it’s fake it till you make it or brush it up and make it look a lot better than it is. And then once they start thinking, Oh, hold on a second, I can make money out of this person, we can help each other. And then they’ll get in touch and they’ll come to you.

But I think you have a right. Don’t bother going to any gallery unless you’ve got work to show, unless you’ve got sales on work to show. If you get sales or work to show, you’ll be fending them off because they’ll come to you.

Stuart: And also, how important is it to know your target market and for example, with your work, do you think geographically there’s a certain kind of market for you or demographically? Do you think about that a lot?

Dave: Yeah, I do. It’s easier for me in one respect because I do a lot of stuff like maps with New York Is Always A Good Idea. I know anybody that’s been to New York and has felt it was a good idea would probably want to buy a print that says New York Is Always A Good Idea. I can be quite, maybe it’s been cynical, I dunno. But I love regurgitating these things and I know that if you put an emotional message like Let’s go get lost together or Is always a good idea, or I fucking love this place onto a map that’s relevant, people will buy it. When I do a lot of stuff, I’ll do an edition. At the moment, I’ve got an edition called Norf Sarf, which is big London maps with Norf and Sarf, written across it and split by the river. And if you are from London, that’s what it’s all about. If you are from the north, you’ll want more Norf on it. If you’ve lived north or south, you want a bit of both. And I just think it’s understanding what are the things that remind me of London and a big part of these things are driven by where I’m from and my parents are.

My dad’s Italian, my mom’s Danish. I don’t feel English, Danish or Italian. I feel sort of slightly like I’m floating in a sea of confusion, but I’m from London and I love that thing of place and sense of belonging and sense of location, but also language. I love the thing about language that will completely change. My kids are talking a completely different language than I did when I was their age, and it was only 30 or 40 years ago. And there’s something really funny about that, that if you’re of a certain age, how old are you?

Stuart: 50.

Dave: Right? Okay. So I’m a bit older than you, but we came from that same generation where there were those words, there were those football chants, there were those TV programs, there was that music, fashion, whatever it is. If I said, shit kicker shoes, you’d probably know what I was talking about. If I said that to my kids they would look at me with a blank face. Sausage on a fork. All of those things were kind of seminal moments. So I love playing with that and creating that emotional connection.

Stuart: When you do that and you make certain cultural references and kind of think who that’s gonna appeal to?

Dave: Yeah, completely. You have a rough idea that there’s gonna be an audience of people that will like it, but I’ve fucked up as many times as I’ve succeeded with this sort of thing. I know for a fact that if I do, Paris Is Always A Good Idea, they’ll sell pretty quickly. If I do, New York Is Always A Good Idea, they’ll sell pretty quickly. New Orleans, maybe not so much. London, absolutely. If I do maps of Newcastle or maps of Glasgow, they’ll go pretty good. And I did a lovely, alright you can, on a big map of Glasgow in gold leaf, it looks beautiful and it went within seconds of putting it on my site. But again, I’ve got the numbers for me because often when I’m doing these things, they’re like one off. So I’m not trying to sell an edition of 25 or 50. I’ve got three or one, and so the odds are in my favour a little bit.

Stuart: So that’s quite important, isn’t it? Like that scarcity. Because you are printing on original maps, then by definition you’ve got that scarcity. Is that right?Dave: Yeah, I do editions. So the Norf Sarf stuff, I’ve got probably about 25-30 original maps that are beautiful, that are pre printing Norf Sarf, Norf and Sarf, and Sarf West on a couple. But I’ve also got an edition of 500 of Norf Sarf, a scan of a map and then I printed it and you can do Giclee and all that kind of stuff. But obviously for me, the thing I love is those original maps that have got that texture and folds and stains and when you get something like that, it’s gold because somebody else has defaced a beautiful thing anyway. But I love that thing of finding something that’s got a story to it. I know no idea what that story is. It’ll hopefully be a private place in somebody’s house rather than sitting in a box in an antique shop.

Stuart: Obviously one of your sort of core strategies is exhibitions, right? And how many do you do a year roughly?

Dave: Probably two or three. I’ll do fairs sometimes, which are quite good fun. It’s really nice to do a little tabletop fair where you get to meet other art fairs. And I do the East Art Fair, which is a really nice one in Spitalfields. And it’s just nice because you get, it’s old school, you get a table or a little cabin and you put your work and you might do a launch of a new edition, but you get to meet people who fucking like your work. Whereas when you’re selling stuff in a gallery, you never get to meet anybody. And it’s a slightly padded version of the relationship. But meeting the people who like your work is a really nice thing. It’s probably very narcissistic, but I dunno.

I think there’s something really nice about understanding who your audience is. And I often find it a little bit surprising because I think all artists start in the same place, which is you’ve got this drive and this yearning to make things that you want to do and that hopefully other people will like. And then when you get into that thing where lots of people really like my work. And suddenly you get those people a bit like some of the people I work with in advertising. You suddenly go, Hey, I’m like King Midas. Whatever I do is gonna be amazing. And so then I start to not really worry about the people who buy my work anymore. And I just deal with the galleries and I’m too big to do a little tabletop fair.

There is something beautiful about the kind of democracy of making good art available to all and not being too poncy and not being too much of a twat that’s gonna think I’m above all of this. And I just love those, East Art specifically, just because it’s in an old market, Spitalfields market, where I used to live opposite and I’ve got an affinity with the market, but I think there’s something really nice about fairs and shows that celebrations of the work and celebrations of the people who like your work. And that’s an amazing thing.

Stuart: Yeah, absolutely. Do you find that people who buy your work through art fairs then become sort of collectors over a longer period of time?

Dave: Yeah, I mean I think there’s always that thing in the back of everybody’s mind, which is, if I’m buying it for 50 quid, 80 quid, 200 quid, 5 grand, is it gonna be worth something at some stage? And we’ve all been in situations where you hear those stories about Banksy selling stuff for 20 quid and it’s now worth 50 grand. So that’s everybody’s dream. But also I think there’s something really nice about when you buy stuff, just buy it cuz you like it in the same way that you would do a pair of shoes, a throw, a sofa, a film at the cinema, buy it cuz you like it. If it ends up being worth something one day, good for you. But more often than not.In a way I think that’s also the role of the artist is how do you make that piece of work feel more valuable? And if you are fun or if you are creating a lot of work or you are doing lots of shows, there’s an added value to that, which is people might think, Oh, this person’s going somewhere. I think I might follow them and there’s a reaction and I met them and they’re really nice to me and they were polite. I don’t know, I think it’s just a bigger brand thing, which is you can be distant and brilliantly creative. I like meeting people and talking to people and kissing dogs and just having fun. It’s also because I’m 58 and I don’t feel like I’ve got time to be precious. It was never in me anyway, but I don’t have time. I love having fun making stuff, and I’m quite happy if somebody said to me, you’ve got another 15 years there and then you’re gonna drop dead. I’ll be like, fucking mate, I’ll take it.

Stuart: Yeah. It’s really valuable actually having that face to face or even just online interaction with people where I do it at theprintspace. I do customer service quite regularly. And that’s where I learned the most about the business. And people say, I really like this, but I hate that. You can sit up high and you can say that I don’t need to do that anymore. But yeah, that’s definitely where you learn.

Dave: There’s such a great life. It’s such a brilliant life. Imagine if you ended up doing the thing that you love doing more than anything, which is coming up with an idea, making it, and then meeting somebody who likes it even more than you and wants to give you their money for it. It’s orgasmic. Now if you’ve got so big-headed that you thought, I don’t need to meet that person anymore. I’m quite happy with that. I’ve done what I need to do and that’s enough. Cuz I’m a superstar. It just feels a little bit shallow and a bit empty. I dunno.

I just think that every artist has got that child, that nervous, that slightly paranoid child inside, which is I’ve got this thing fucking pushing me to do stuff. It even makes a hair on my arm stand up when I think about it because from an early age, from 3, 4, 5 years old, my mom kept all my sketchbooks and that’s all I ever did was just doodle and draw and make, and now I’m 58 and I’m still doing the same thing. It’s genetic. There’s something in me which made me do that. And all artists have that. All artists have that horrible paranoia that I’m no good and that I’m gonna be found out. But when I get it right and when it’s good, I’m the fucking most important person in the world. It’s that the highs and lows of being creative and the terror of coming up with an edition, investing load of money, of your own money in it, and then hoping that some other people will buy it quickly, cuz that would always be nice. You don’t want to be sitting around on shelves for two years and the sheer fucking panic of thinking, God almighty, I just dropped ten five grand, 700 quid, whatever it is into this piece of work. And then it doesn’t sell and it’s, oh my god.

Every time I do a fair, I’m sitting there thinking, I hope it’s good, I hope it’s good, I hope it’s good. And then when it’s bad, you just go take a punch, have a cry, smoke a fag, get on with the next one. And when it’s good, you do exactly the same. Have a glass of wine, don’t get carried away by yourself, do it again. And you just get into a routine and, I dunno, I think it’s an amazing feeling and I think I’m so fortunate to be in that position where I can do that as my job compared to what I was doing before. I was pulling my hair out every 20 minutes trying to like crossing the beach at Omaha. Whereas now it’s like everything is about flourishing and about being, and about creating and it’s an amazing thing to do.

Stuart: Yeah, fantastic. I always like to finish off by saying, is there two or three pieces of advice you would give to somebody starting out now who wants to emulate what you’ve done and make a career out of their art?

Dave: Yeah, I think it’s to do some homework. Don’t just jump in. Create a kind of format for how you want to achieve success or happiness or fulfilment, whatever it is you’re after. Work out what you’re after, but then do some homework. Find out, work out what you’re good at, what you’re not good at. Stop doing what you’re not good at and do more of what you’re good at. Keep it simple, stupid. It’s real KISS stuff. And then be professional. Do it on time. Turn up on time. Be polite. It’s all simple shit that I’d had grilled into me when I worked in advertising. But I think the most important thing is just do the fucking work. Do the fucking work and just keep going because it’s easy to get despondent. And I talk to a lot of people. I love helping, mentoring and I do some stuff with a company called Wiser and where I talk to a lot of people who are similar to me, who are working in design or advertising or whatever it is, and they’ve got this thing on the side that they want to make their thing. And I have this conversation with them every time, and it’s just never, ever give up.

If you believe in it, do it. It’s the most amazing feeling you have got. You’re running out of time. You get 80 summers if you’re really lucky, and just don’t waste it. Just make sure that you are constantly doing it and having the most fun you can have. And then if by hard work and by organization, and by fucking constantly banging the same door, that doorway opens and you end up doing something that changes your life, which is exactly what it did to me, then good for you. But you earn it. And I think it is just about doing the work. It’s a cliche, but when you’re doing art and you are doing what you love doing, there’s no work involved. It’s literally just fucking about all day long. You just get to do exactly what you want. But to get into that situation where you can pretty much do exactly what you want, you’ve just gotta listen to a load of people and understand and bounce off them. And eventually you’ll get on that route, which will take you to where you could be. And then just fucking keep going. And stay off the crack, stay off the drugs. That’s just a terrible distraction. I’ve never done any of that stuff, but all of the smart people I’ve known that have been on that shit always fuck up.

Stuart: Yeah, it’s usually when bands fuck up as well, isn’t it?

Dave: Yeah, totally because they get carried away and they think all of a sudden I can do anything. I do a lot of coke. Suddenly you’re doing heroin, and then you’re doing all sorts of nonsense and you’re fucked.

Stuart: Brilliant. I can’t thank you enough. Fantastic advice for anybody and we look forward to your next show, which is in a few weeks time.

Dave: Also, if there’s anybody that you get messages from, people that want to talk about anything else that we’ve half covered. Mentoring is a big part of it. Giving them any advice, understanding whether they need a kick up the arse or they need an arm around the shoulder or they need just some general good advice, at every age. We all need it and I just think it’s really valuable. And for me, I had a lot of that when I worked in advertising, and I had a lot of that when I got into the art side. And there were fundamental moments in that meeting and that conversation and that moment that fundamentally affected my life. And if you are yearning to be an artist, it’s a big step because we often end up doing something else to pay the bills. And it’s possible. It’s possible. You’ve just gotta formulate a plan and then apply it. And then like I said, don’t give up.

Stuart: Fantastic. Thank you very much. And yeah, we’ll definitely pass on your details to anyone who wants ’em. And thanks again, Dave. It’s brilliant.

Dave: Pleasure. Thanks.